Laminitis is a devastating and all too common condition that affects horses worldwide. It is a complex and painful disorder that involves the inflammation and breakdown of the sensitive laminae within the hoof. It’s not only causes excruciating discomfort but can also lead to permanent damage and even life-threatening complications if left untreated. In this blog post, we’ll looking into the intricate details of laminitis, exploring its causes, symptoms, treatment options, and most importantly, preventative measures for all horses.

What is Laminitis?

Laminitis is a painful and debilitating condition that affects the hooves. It is characterised by inflammation and damage to the laminae. The laminae is a interlocking tissue that connects the hoof wall to the underlying structures of the foot, including the coffin bone.

The laminae also anchors the coffin bone against the pull of the deep digital flexor tendon, therefore playing crucial role in supporting and stabilizing the horse’s weight.

Due to a various causes, inflammation begins within the laminae, which can lead to cell death. Blood is moved away from the foot, which results in the strong digital pulse seen in laminitic horses; As the laminae become damaged, they become weak, and therefore cannot keep the coffin bone in place. As this happens, the coffin bone gradually shifts forwards towards the sole of the hoof.

Laminitis can occur suddenly or develop gradually over time, and it can affect one or multiple hooves. The condition can vary in severity, ranging from mild lameness and discomfort to severe cases where the horse is unable to bear weight on the affected limb(s).

There are several factors that can contribute to the development of laminitis. These include:

Dietary Factors:

Overconsumption of starch, lush fields, or a sudden change in diet can lead to an overload of carbohydrates and sugars in the digestive system, triggering laminitis.

Metabolic Conditions

Horses with metabolic disorders such as equine metabolic syndrome (EMS) or Cushing’s disease are more prone to laminitis.

Trauma

Direct trauma to the hooves, such as excessive pounding on hard surfaces, can cause laminitis.

Endotoxemia

Systemic infections, colic, or severe illnesses that result in bacterial toxins entering the bloodstream can induce laminitis

Supporting Limb Laminitis

Laminitis can also occur in the opposite limb of a horse that is bearing excessive weight due to lameness or injury in another limb

Clinical Signs of Laminitis

Lameness

One of the most notable signs of laminitis is lameness, which is often characterized by a stiff, short stride, and the horse’s reluctance to move. Laminitis-related lameness can affect one or multiple hooves.

Digital Pulse

An increased digital pulse, commonly felt at the back of the pastern (above the hoof), can be an indicator of inflammation and blood flow disturbances associated with laminitis.

Hot hooves

In the early stages of laminitis, the hooves might feel warmer than usual due to inflammation and increased blood flow.

Shifting

Horses with laminitis often shift their weight between their hooves, leaning back to relieve pressure from the painful front feet.

Horses with laminitis may also exhibit reluctance to walk or turn, as the act of movement worsens the pain in their affected hooves.

Movement

Horses with laminitis may exhibit reluctance to walk or turn, as the act of movement worsens the pain in their affected hooves.

Rocking

To alleviate the discomfort in the front feet, horses may adopt a “rocked back” stance, with their hindquarters positioned further under their body and their front feet extended forward.

Hoof Pain

Horses may react to hoof testers or other forms of hoof pressure more dramatically than usual due to the increased sensitivity caused by laminitis.

consequatur.

Fever

In acute cases of laminitis, a horse might run a fever as a response to the systemic inflammation associated with the condition.

Prompt veterinary intervention is crucial. Treatment typically involves a combination of pain management, anti-inflammatory medications, and therapeutic hoof care to relieve pressure and promote healing. Managing underlying causes, such as adjusting diet and addressing any metabolic issues, is also essential for long-term management and prevention of future episodes.

Prevention

Prevention is key – maintaining a balanced diet, carefully managing access to pasture, monitoring weight, and providing regular exercise are all essential in minimising the risk.

Feeding

When selecting what to feed a horse with laminitis, it is important to consider a few key factors. It is recommended to keep the horse’s diet low in sugar and starch, ideally less than 10%. This is due to the link between hyperinsulinemia and laminitis risk. You can also consider sending your hay or haylage off to be analysed to see how much sugar and starch is present in the hay. It is also recommended that hay is soaked before feeding to remove excess sugar. It isn’t recommended that you soak your haylage as this can lead to secondary fermentation.

It is important to keep horses prone to laminitis at a healthy body weight due to excess weight causing strain on laminae structures. If a laminitic horse needs to gain weight, we recommend feeding a high oil feed such as unmolassed sugarbeet as this does not significantly increase insulin levels in the blood.

As most laminitic horses are on a restricted diet to prevent weight gain, their vitamin and mineral requirements are usually slightly higher as they are not eating as much forage. Supplementing biotin is also recommend to support healthy hoof growth.

Body Condition Scoring Guide

At home weight monitoring can be hard but body condition scoring is a simple and easy way to keep track on your horse’s weight.

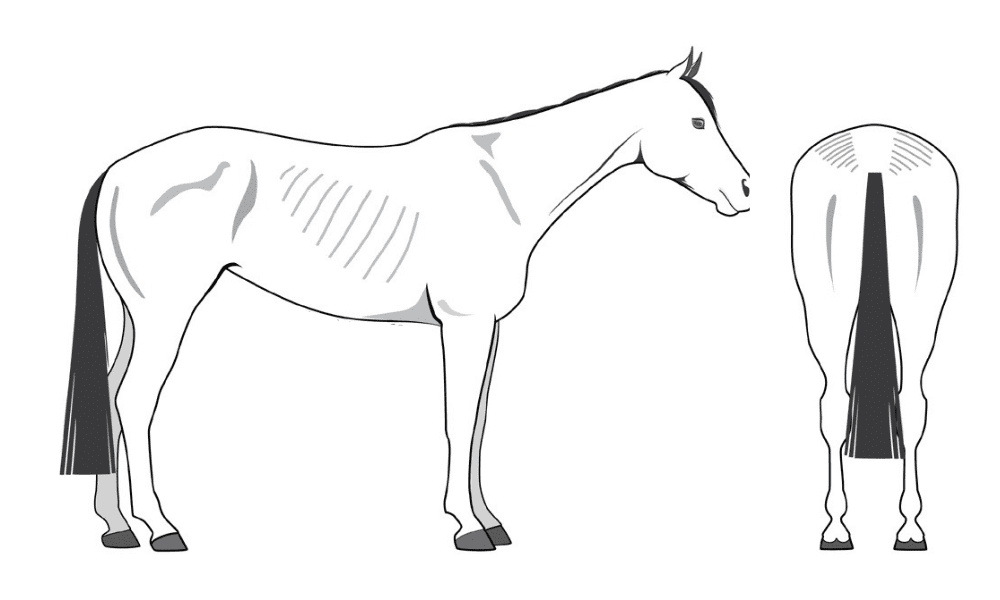

0 = Emaciated

No fat can be felt. Very thin neck, with no topline, bones are visible, sunken hindquarters with prominent backbone, pelvis and tailbone

1 = Very thin

Barely any fat can be felt. Narrow neck, with very little muscle and fat. Shape of bones visible. Sunken hindquarters, prominent backbone, croup and tail head.

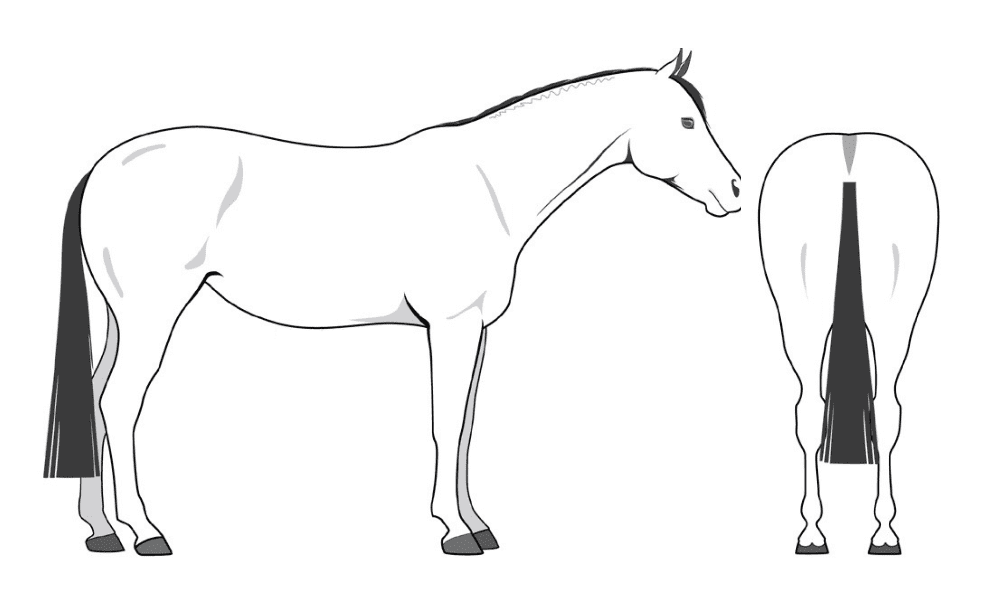

2 = very lean

Very thin layer of fat, narrow neck with sharply defined muscles. Ribs are just visible. Hindquarters are sloping, hipbones are easily visible but covered by a thin layer of fat.

3 = Healthy Weight

Thin layer of fat can be felt. Muscles on neck are less defined. Ribs are not visible. Backbone is covered by fat. Hindquarters are rounded. Hipbones are slightly visible.

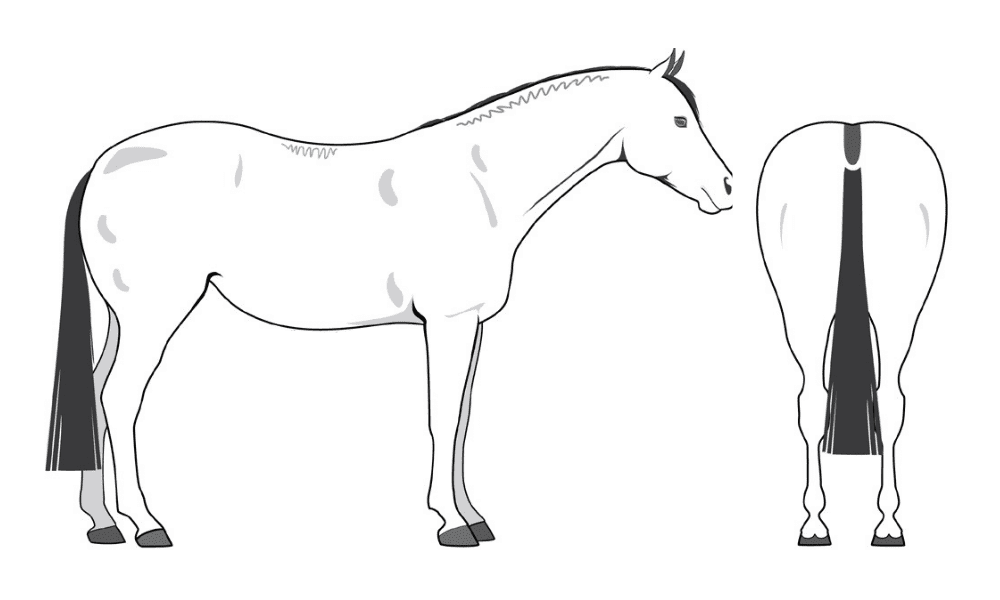

4 = Fat

Muscles are hard to determine. Spongy fat on neck. Fat can be seen behind the shoulder. Ribs, Pelvis and hips are difficult to feel. Hindquarters are rounded with fat. A gutter can be seen along the backbone.

5 = Obese

Visible pads of fat with no muscle. Cresty neck. Ribs and hips cannot be felt. Deep gutter along backbone. Lumps of fat around tail. Bulging hindquarters. Inner thighs press together.

In conclusion, understanding and preventing laminitis is a key issue in equine health. Laminitis can strike without warning, but by recognising the early signs, implementing proper management strategies, and seeking prompt veterinary care, we can help prevent future cases occurring.

Any questions about nutrition and laminitis? Contact our friendly expert nutrition team at nutrition@purefeed.com or call us on 01458 333 333.

Let us help you cut through the chaff – request a FREE bespoke diet plan today.